The Markas – An Anthology of Literary Works on Boko Haram | A Review by Françoise Ugochukwu

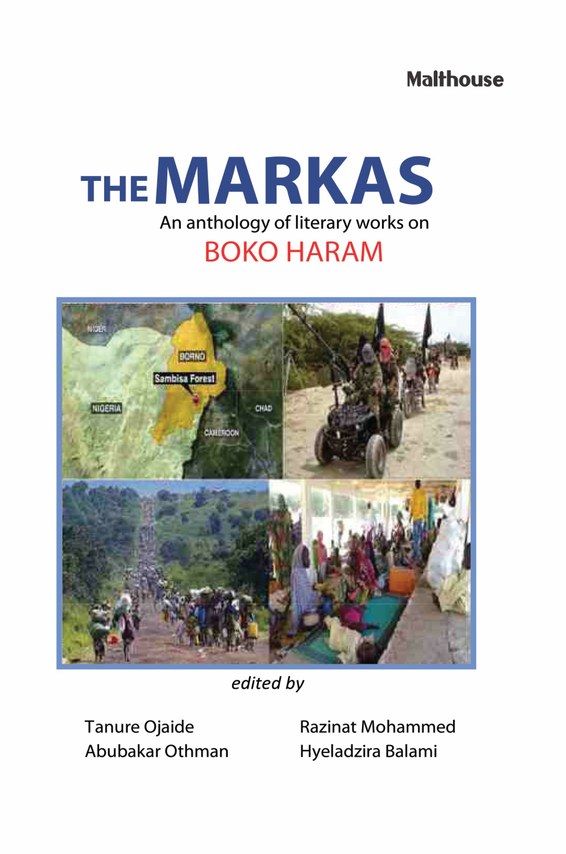

The Markas is the first anthology on the Boko Haram insurgency, which has blighted northern Nigeria for the past 10 years, causing the death and dislocation of millions. Responding to the perceived world’s apathy, its “loud silence” (pp.16-17), and the absence of memorabilia, the four editors, three of whom are posted at the University of Maiduguri in northeast Nigeria, have taken to literature to attract global attention to the crisis, using the name of the site of the Markas, near Maiduguri. They gathered texts from 28 contributors (15 male, 13 female), most of them already confirmed and published writers.

Three of the authors, Razinat Mohammed, Abubakar Othman and Tanure Ojaide, contributed 4 texts each to the various parts of the anthology. The 4 pages devoted to the contributors’ bios confirm that the conflict has affected the whole of Nigeria’s States and ethnicities – contributors come from all corners of the Federation, from Abuja and Lagos to Enugu and Maiduguri, from Bayelsa, Borno and Gombe States. It also reveals the vibrant literary scene of this vast country: Agema Vershima and Folu Agoy are both editors and award-winning authors. George Chukwu is a prolific blogger. The link between Universities, the teaching and literary sectors is equally highlighted: Ruth Bariki just finished her Master’s degree, Hassana Maina, Zugu Amstrong and Abubakar Joda are students in Law, English and Pharmacy. Vicky Sylvester, Audee Giwa, Jummai Mustafa, Tadi Yerima and Adama Idrisu lecture in universities. The presence, among the contributors, of a marriage counsellor and of a federal disability mobilisation officer, reinforces the message of the widespread revulsion at the Boko Haram continued violence.

The volume is dedicated to all those affected by Boko Haram in their socio-cultural, economic and political lives, and divided into three parts, two of which are devoted to poetry, while the third offers eight texts gatered under the title “fiction / non-fiction”, revealing the reality hidden under the fiction. The introduction offers a definition of Boko Haram and gives a brief history of that movement, started as a Qur’anic school with Kanuri elements in 2002 before the violence of its members started tearing apart the neighbouring States of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa from 2009, and bringing about the declaration of a state of emergency in 2013 in those three north-eastern States of Nigeria.

The editors’ first concern is to highlight the ramifications of the movement in Mali, Niger, Chad and Cameroon, and reflect on the causes of the insurgency: they quote the poet Shehu Sani on the subject, suggesting that Boko Haram has been fuelled by a combination of some 20 factors, including poverty, social inequality, Islamic jihad teaching, regional unrest, governmental negligence, the Nigerian army’s incompetence and the desire to fight corruption. Possible solutions to restore peace are then listed, including the dialogue, considering the failure of military efforts. Yohanna suggests learning Arabic to communicate (p.77). But none of these solutions seems reasonable. The value of the volume lies outside this brief academic presentation, in the powerful and heart-wrenching account gathered from poems and prose texts loaded with contrasts, whose words keep echoing each other.

The poetry section might well have adopted one of Diana Eke’s poems as a title – “Centenary Condolences”: “Condolences, my country, condolences. A 100 tears for your hacked men and women, another 100 for your youth. […] in the implacable half of a yellow sun” (p.57/58). [I1] The poems contextualise the situation, mentioning Sudan, Egypt and Libya, while contrasting past and present, the sweet dates of Markas, the “metaphor of life” (Othman: 43), and the daily experience of death and destruction affecting all those living in these parts. Some words keep reoccurring in that blood-soaked landscape: Kaduna, Kano – the two neighbouring states’ capitals, then Maiduguri – capital of Borno State, the Sambisa forest, Chibok. Other keywords served as landmarks, with their repetition contributing to weave a web of destruction – tears and cries, general insecurity, killing and disappearance, broken pots, disorientation, abandonment and nightmares. Line after line recalls emaciated children “in the nest of tears” (Imam: 17), torched villages, orphans and refugees on the road, bereft families threatened by hyenas, vultures and rodents on the rampage, and cries of agony from the forest.

The poets lament the girl bomber “too young to understand” (El-Mubashir: 44), and struggle to explain the Boko-Haram killing “in the name of God and country” (Othman: 42). Their explanation is that of “a Holy Book turned upside down” (Giwewhegbe: 27). The terrorists are the real ‘infidels’ who profane the word “God is great” (Yohanna: 79), they “have no religion, no faith” and are neither human nor beasts – just mosquitoes. Then, there are additional worries: first that, not so long ago, the “Beasts were babies” “one of us” (Kaase: 69), Southerners, who have been victims too, are accused of inertia, they that “raise hell only when churches are bombed in the north [but] look away when the victim is a non-southerner” (Eke: 54). Salawu remembers the past when a child belonged to everyone: If you harmed one, you harmed us all. That was love, before. In the end, the only way out is prayer: “when is the end?” (p.64); “God deliver us” (Zugu: 19); another poem ends with the Igbo night salutation: “May our day break!” (Vincent: 82). All they wished – farmer, pupil and housewife – was a normal life. In the midst of blood and tears, rare, moving images reveal the resilience of a population whose hope of return, peace and renewal, expressed in Amajuoyi’s poem Ode to Leah Sharibu “the teenage amazon”(p.36), is still alive. Amina shares her lunch with Mary: “because innocence knows not friend or infidel” (p.60). The volume is a wake-up call which testifies to the determination to keep speaking “through silence […], through tears and wounds” (p.32) to raise people’s awareness. In a carefully choreographed sequence, the very short second part (8p.) of the collection, presented as an appendix to the first part, engages the conversation between poets, presenting five poems which talk and respond to each other on the subject: “the fear of Boko-Haram is the beginning of wisdom” (p.92), confirming poetry as a powerful communication tool.

The third part (89p.), born of the same agony, lines up eight short stories which help readers penetrate deeper into the northern landscape, focusing on the devastating impact of violence, abduction, displacement, unwarranted killings and rape on families. Two of these stories are written by the two most represented editors and contributors, both from the University of Maiduguri, Mohammed and Othman. Each of the titles contributes to the assembling of a puzzle, piecing together fragments of stories from this embattled landscape: My Daughter, My Blood raises the timely, painful issue of returning abducted school girls impregnated by Boko-Haram. The title of the third story, Home is No Place to Stay, summarizes the entire book, offering the heart-wrenching reflection of another couple whose daughter has also been abducted but never returned. In Dashed Hopes, a widow laments the loss of her legs in a blast. Other stories consider other faces of the issue: Rite of Passage reveals the deleterious effects of corruption in displaced persons’ camps in Borno, seen through the eyes of a Yoruba volunteer. Flying over the Crises puts into words the reality that for victims, “death had become a constant companion” (Giwa: 150) while considering “the postulations that most of the NGOs grew fat on the Nigeria’s north-eastern crises […] without adequately doing anything […] to alleviate the suffering” (Giwa: 149). Command and Compliance shows the uneasy relationship between the university and an army abusing its power. They Call Me Helen helps readers get under the skin of a traumatised displaced girl, rescued from the north and “grateful for getting another second, minute or week to live” (Maina: 158), only to end up raped and impregnated by a school teacher. The Long and Empty Road, the only text bringing in politics into the mix, describes the two major parties, PDP and APC as “two faces of the same coin” (Sylvester: 173) and concludes that “the military seem unable to cope with the insurgents […] better equipped” (p.176). This anthology put together by insiders from Nigeria is definitely a precious testimony on an often forgotten conflict.

Françoise Ugochukwu

(Open University, UK)

This book review is published in: Africa Book Link, Fall 2019