The Day Ends Like Any Day | A Review by Sola Adeyemi

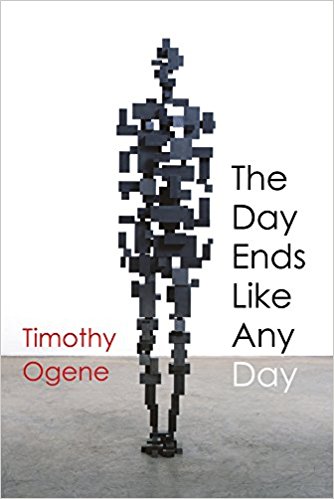

Timothy Ogene, The Day Ends Like Any Day. Berkshire, England: Holland House, 2017, pp.264. ISBN: 978-1-910688-29-8 (paperback); 978-1-910688-30-4 (kindle)

The Novel that Ends like None Else

There is no sun today,

save the finch’s yellow breast,

and the world seems faultless in spite of it.

Across the sound, a continuous

ectoplasm of gray,

a ferry slits the deep waters,

bumping our little motorboats

against their pier.

The day ends like any day,

with its hour of human change

lifting even the chloretic heart.

– “A Half-Life” by Henri Cole (http://www.theartdivas.com/2014/02/a-half-life-by-henri-cole.html)

The ninth line of Henri Cole’s poem is an inspiration for the title of Timothy Ogene’s novel, The Day Ends Like Any Day, published by independent publisher Holland House in 2017.

The novel is divided into three parts, with an epilogue. Part one is about the early years of the protagonist; part two is the coming of age years at the university; while part three is devoted to the relationships that Sam, the protagonist, forms during his university years and how they influence his life and experiences. The epilogue is ‘written’ by one of these friends, Osagie, who presents a revealing commentary about Sam’s life.

But, I am getting ahead of myself.

Growing up in Nigeria is always a multicultural experience as most communities are hubs of diversity. Recuperating experiences of living in such communities can be an amalgam of the amazing, the bizarrely wonderful, as well as fabulous tales. This can make a bildungsroman emerging from those experiences both credulous and incredulous, familiar and strange, but writing that the reader can identify with; and adventures that rouse a reader’s memories of their own childhood.

Timothy Ogene’s The Day Ends Like Any Day is a bildungsroman with familiar adventures and surreal experiences. This is a lyrical, vibrant, and challenging coming-of-age account of the multiple identities and multiple personalities of a young Nigerian growing up in a period when everything around him is changing but who refuses to accept that his life has been formed by the traumas and dependencies of his life and past. What makes the tale striking is that our hero grows up in Nigeria trying to find a new direction under dictatorship of the 1990s, after years of wilful neglect of the needs of its citizens.

The above are strong statements that require unpacking through an analytical review of the book. But before I continue, let me confess that The Day is one of the most interesting and unputdownable books I have read in the past several months. It resonates powerfully with my experience of growing up in Nigeria – even though the setting of the book is more than 600 kilometres from my childhood area – and some of the incidents described are not only familiar, but they seem to have happened to people whose acquaintances I had.

After that self-declaration, let’s look at what makes this book good, readable, or perhaps even tedious.

The Day is about Sam. It starts with Sam growing up in Oyigbo, near Port-Harcourt, a vibrant community only identified as O. in the book. The author’s choice of “O” could be a distanciation technique, as there are several towns around Port-Harcourt with names beginning with O, such as Okrika, Ogbogoro, Old Bakana, Onne, or Ogoni, to mention a few. However, the description of the blocks of residence and the environment recognisably describes Oyigbo, “lying east of Port Harcourt, south of the new highway [A3 motorway] that runs from Aba to Port Harcourt, and west of the murky Imo River” (p. 8). This is where the author grew up, and where our protagonist also grew up in a “room-and-parlour affair”, a two-roomed apartment in Block V, Room 7, a place with leaky roofs and cracked walls which are bordered by clogged drainages. This is the environment where Sam the protagonist weaves a vista of narratives that introduces us to exciting and unforgettable characters: his sceptical sister, Ricia; Pa Suku whose mentorship capability moulded Sam into a book lover and thinker; the cantankerous Ma Ike; Dan, the mysterious tailor’s son who has the knack of appearing at eventful moments and vanishing before trouble erupts; the enigmatic and incorrigible womaniser Jide, the only resident with a television set; and pregnant Dora who one day walked naked into a lake, drowning herself. The traumas of life follow Sam from O. to Delta State University where encounters with lover Margaret and musician friend Osagie question his sexuality and sanity.

The narratives constantly shift between the past and present, through metaphors and imagery that traverse the spaghetti routes of memories. Sam’s journey through life is described as it progresses forward whilst still rooted in the past and presents vignettes of emotions in cyclical and repetitive moments. For the author, this is more of a coming-of-language novel than coming-of-age, as he finds new imagery and new language to define Sam’s experiment with life. As the title of the novel suggests, the days become not a flow of time-limited sequences, but an eternal present that shrinks or expands through the power of our own mind. Our understanding of identity is challenged as we battle with factors that shape and define Sam but are reflected in his various encounters and unspoken thoughts. We are convinced that personalities are never identities that are built and fixed but are combinations of several identities; some belonging to us and many belonging to others; our dreams and aspirations; and our past, especially moments that tweak our imagination, such as the suicide of a teenage friend. In the end, we realise that we can never escape ourselves or the components that define our personality. And that is what Sam realizes in this psychological novel of formation.

This is a highly recommended book though description of places and landscape sometimes interrupts the action and the flow of the story. Perhaps this can be excused in a first novel. What however distracts are the grammatical errors and anachronism. For instance, an example of anachronism relates to Pa Suku: “…by the time I was in senior secondary two, that fantasy was swept away by literature” (p. 59). This is in reference to the Universal Basic Education programme in Nigeria – locally termed 6-3-3-4 – whereby pupils spend six years in primary education, followed by three years in junior secondary and three years in senior secondary, and concluding with a four-year university education. However, this programme was introduced in 1988, and given Pa Suku’s age inferred from his war experience and gap to Sam’s he would have studied under the old system of a five-year secondary education without a demarcation.

“Ricia continued to bounced along…” (p. 16); “Those where the good old days…” (p. 60); and “I awoke to Mama’s face staring down at me. had been kicking…” (p. 95) are some of the errors (in bold) that the editor missed. And, I can even pretend to understand what this is supposed to mean: “I have alternativeiivenge viewsay through Agbor, c.meant:April, 2017.I work views on everything” (p. 138).

Nonetheless, this is a highly lyrical – although not described as a memoir or an autobiography – and refreshing prose that paints the past in layers of memories. It certainly announces Timothy Ogene as a new literary voice from Nigeria.

Sola Adeyemi, Goldsmiths University of London

This book review is published in: Africa Book Link, Spring 2018