Stanley Gazemba on mermaids and how to prevent us from turning into robots | An interview by Elke Seghers

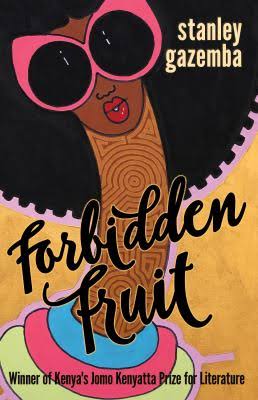

I interviewed the Kenyan author Stanley Gazemba on the occasion of his 2002 novel The Stone Hills of Maragoli being republished in the U.S. under the title Forbidden Fruit (June 2017). In April 2017, we had a conversation about his work and the Kenyan literary landscape at the Go Down Arts Centre in Nairobi, where Gazemba is the editor of Ketebul Music.

ES: As I understood it, Forbidden Fruit is going to be published soon.

SG: Yes, although in fact, Forbidden Fruit is not a new book, but was published in 2002 as The Stone Hills of Maragoli. The whole thing was quite an adventurous journey. It was first published by Acacia Publishers, which was at the time newly founded by someone who had left East African Educational Publishers. I had actually first submitted the manuscript to the latter publishing house, but Acacia picked it up. From the very moment it went to print, I started hearing rumours that the judges of the Jomo Kenyatta Prize had taken a liking to it. The book was competing neck to neck with a submission from East African Educational Publishers. However, the judges liked the book and in 2003, The Stone Hills of Maragoli won the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature.

ES: What did winning the Jomo Kenyatta Prize mean for you?

SG: It helps your reputation as a writer, but it also creates problems. When I won, I received 50 000 shillings. But everyone had seen my face in the newspaper. So, if you walk into a pub, you have to buy the drinks. Your friends and your neighbours look at you differently, they think you are rich, when in reality, not much has changed.

ES: Do you think there should be more initiatives for Kenyan writers?

SG: I think, first of all, there is a need for sincerity. It feels as though publishers manipulate these prizes. I am told East African Educational Publishers were really rooting for their guy to win. As my publisher was small and was a competitor that had branched off from East African, there were a lot of things playing against me. I am told that publishers also pay bribes to the Kenya Institute for Curriculum Development to have their books accepted for the school system. Of course there’s no evidence to support this. All the same it is a rotten system and it is hard for authors to operate in such an environment. Maybe this is something that happens all over the world in publishing, but I think it is very discouraging. You cannot build a proper literary culture based on people pushing brown envelopes. Writing can only grow when the guys at the top are there because they deserve it. There is also the problem of piracy. There are a lot of pirated books on the market and the fines are relatively low.

ES: What happened after you won the Jomo Kenyatta Prize?

SG: Unfortunately, Acacia Publishers went bankrupt. After some time, Kwani? Trust decided to publish the novel. As Kwani? is an NGO, everybody had a fixed salary rather than a commission. I felt as though they did not make much effort to sell the book and I got frustrated with them. I was doing a lot of marketing myself. Publishing in Kenya is all about getting a book into the school system, so I was going to classes to talk to the students and sell some books. The book became a set text in quite a number of universities, mostly around Nairobi. But when my royalties started coming in, they did not reflect my efforts. That is why I decided I needed to find a serious commercial publisher.

ES: I understand you did not have an easy relationship with your publishers.

SG: I have had the same problems with almost all of my publishers. They are keen on putting books out but do not make much effort afterwards. Furthermore, they do not pay people on time and do not invest in promotion. That is the reason why I reached out to an American publisher. I met my American publisher last year at a festival in Uganda. At the very last day of the event, I decided to show him my book. He read the book on the plane home and he liked it. I immediately got an email to say that he was very interested and wanted to publish it. Things started moving very fast and I think it is now in print.

ES: How do you feel about reaching a new audience?

SG: I meant to break through internationally this year. Right now as we speak, I was supposed to be in Venice to launch a collection of short stories called Dog Meat Samosa. There had been plans for activities in the media over there. Unfortunately, I could not get the visa to go to Italy. This was not the first time I was invited to go to Venice, I was also invited in 2013 but had similar visa problems. The book has been published, but I do not know if it is going to sell well without me being there.

ES: What kind of audience do you target?

SG: I think my prime target is the average person, although I know that you cannot survive without elitist readers, because those are the people with the money; the average reader would most likely access your book from a public library. But that tiny middle class audience is not enough to make something a commercial success either. The reality on the ground is that you cannot survive in Kenya unless you are part of the school curriculum. Ultimately, I want to be successful internationally. I am sure that there is no writer who just wants to be read by his village.

ES: How does that affect your choice of language? You write in English, but use a lot of Luhya words in The Stone Hills of Maragoli. Do you think the only way to be read is to write in English?

SG: I think that is a tricky question. Language is something political. In Kenya, we have no choice but to write in English. English has become a global language and if you really want to be read by a cross-section of readers around the world, you cannot avoid English. But having said that, I find that, although English is widely used in Kenya, there are certain things that we can only communicate amongst ourselves, be it in Kiswahili or Luhya or Lulogooli. I will express the things that I feel deep inside in Lulogooli. The question is how to express oneself in that deep way to someone who does not understand Lulogooli or Kiswahili. Achebe was writing in English but he had his own version, a certain English that can be understood by a British reader, but that is clearly not British English. The challenge on the African writer is to use the tools available to him, but in a way that certain things are twisted to make it convey what he wants to say. If I would use phrases or expressions that I have read in a book by George Eliot, I think I would come across as a fake. The only solution is to use that language but use it in such a way that it is Africanized, bent to suit one’s own. That is why I said language is something political.

ES: Let’s talk a bit about the book itself. I noticed The Stone Hills of Maragoli focuses on life in the countryside and the perspective of the labourers.

SG: I set The Stone Hills of Maragoli in a fictitious village modelled on the village in which I grew up in Western Kenya. It was a deliberate decision. Although I now live in Nairobi, I chose to set my book in the village because that is the only place where you can have a taste of authentic Kenyan everyday life as a visitor to the country. It is very important to me to tell the Kenyan story from the point-of-view of an ordinary Kenyan who walks the dusty streets of the small back-wood towns. It is the reason I choose to root those stories I set in Nairobi deep in the ghettos of the city. One such book is a collection of short stories about Nairobi called Nairobi Echoes. I like to think that the soul of any city is buried in those ghetto places. They are rarely highlighted, but that is where the majority of people live. I am also deeply attached to labourers because I believe they are the engine of any economy- the guys who roll up their sleeves and put the greasy wrenches to the machine’s nuts and bolts, crawling into the belly of the machine to fix what is bothering it. The farmhands who tend to the coffee and the cows are the people who really drive an economy. And they are very open folks too. In middle class Nairobi, for instance, there is a façade; people try to put up a front. They eat their food with knives and forks like white people, whereas if you go to these other places, people wash their hands and eat in the traditional way. It is more interesting for me to observe and write about these ordinary people who are more accessible.

ES: So you want to show life as it is in your writing?

SG: Yes, I want to capture it in its basic form. I came to find that people in the village are much more real, just like in the ghettos. In the kind of stories I write, I create characters from the people I interact with. As a writer, I am always keen to know about someone’s fears, joys and aspirations, about what makes them who they are.

ES: I was also interested in the depiction of the seductive Madam Tabitha. She is described as a creature half-woman and half-fish. Where does this image come from?

SG: The image of a mermaid has always been the centre stage of the discourse of the village and by extension the ghetto. There are always stories of farmers who make money and want to make up for lost time after the harvest season. The farmer moves to the market centre or the local town and books himself into a hotel with a commercial sex worker. The story always ends with the poor farmer losing all of his money to the lady, who oftentimes comes from Nairobi, or, even worse, Mombasa, and is much more wily and street-smart. This narrative of people losing their sanity and wealth to a flashy and attractive lady who drives them mad has never changed. And that agrees with the image of the mermaid who is very beautiful but not quite human. I think Madam Tabitha, as a character, feeds off of all of those stories.

ES: Are there any writers that influenced you?

SG: Chinua Achebe, who I studied in High school, although the experience was a little unpleasant as the system made you cram passages from his books instead of reading for pleasure. The early Ngugi wa Thiong’o used to write very well until Marxism went into his head. I enjoy Meja Mwangi. I also like John Steinbeck’s style although I am told he is an old-fashioned American writer. Ken Follet is very good at creating characters. When it comes to contemporary African writers, there is Ben Okri, Chimamanda Adichie and Nadifa Mohamed, to mention but a few.

ES: As a final question, why do you think literature is important?

SG: I think we cannot do without writers. I do not think there is any society that has developed scientifically without that growth being fuelled by the arts. I think the arts give direction to the other spheres. On that note, I believe the arts are not just, as they are derogatively called in universities, humanities. They are much more. You cannot be a good creator if you do not understand other spheres of life. You need to be an informed person in order to write. Most importantly, if it were not for the arts, we would become robots. What would people look like without culture; without good books, music and theatre? I also believe it is very easy to strike up a conversation with a stranger, for example from a foreign country, if both of you have read such or such a writer or if both of you are interested in the same musical instrument. Those are some of the things that make me believe that the arts are important. Even in politics it is usually a musician who is hyping up the crowd before the politician mounts the stage.

Stanley Gazemba, Forbidden Fruit (Astoria, NY: The Mantle 2017). ISBN 978-0-9986423-0-7. Available from The Mantle; 286 pages

This interview was published in: Africa Book Link, Fall 2017: Eastern Africa